On the 6th of February 2024, a student pilot and instructor met at Gold Coast Airport in Queensland for a dual training flight. The clear lesson learned that day was a common one: if the approach is not stabilised, go around! But to be fair, the instructor did go around, just …a little bit later than most of us would have. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

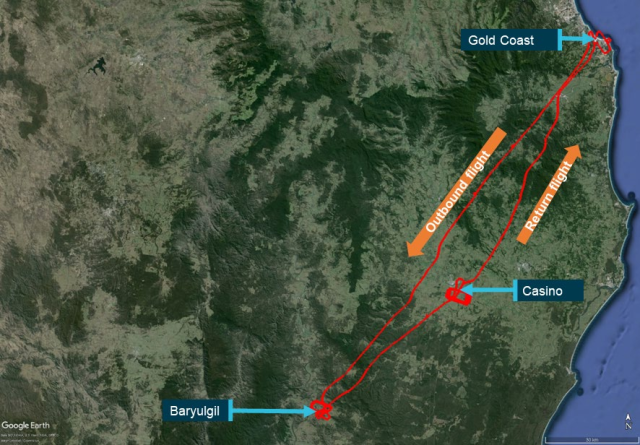

The student pilot and the instructor departed for that day’s training in a Cessna 172R owned by the flight school, registered in Australia as VH-EWW, at about 11:38 local time. The weather that day was hot: 31°C (88°F). The flight instruction was uneventful: they flew to Baryulgil where they did some aerial work. On the way back, they did five circuits at Casino, leaving just before 14:00 to return to Gold Coast Airport. It looks to me like the plan was to finish at 14:30, making for a three-hour lesson.

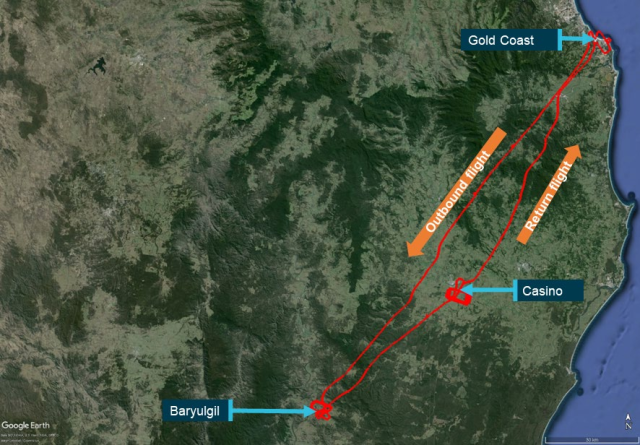

Gold Coast Airport is located at the southern end of the Gold Coast, about 90 kilometres south of Brisbane. The airport and its two runways are about 21 feet above mean sea level. The primary runway, 14/32, was extended in March 2007 to its current length of 2,492 metres (8,175 feet). The second runway, 17/35, is just 582 metres (1,900 feet) and intersects the longer one.

When they were about ten nautical miles southwest of the airport, the student pilot called Gold Coast Tower air traffic control to say that they were inbound. The controller cleared the flight to enter controlled airspace and to track direct to the airport at 1,500 feet, expecting runway 32. Soon after, they were cleared to descend to 1,000 feet. At that point, they were just over 6 miles from the airport and tracking for a right base leg for runway 32, that is, joining the circuit at a right angle to the final approach and runway direction.

There was a Boeing 737 also inbound to Gold Coast Airport’s runway 32 and travelling quite a bit faster. The controller worried that the Cessna might be slow on the approach. For a light aircraft such as the Cessna 172R, the speed flown during the final approach can vary by 20 to 30 knots; at higher speeds, the pilot will slow just before touchdown for a more consistent landing speed. The controller knew that student pilots often come in slow, which might mean that the Boeing 737 would have to go into a holding pattern or go around while the Cessna landed.

He called the Cessna 172R to ask if they could “accept runway 35, best speed” in order to keep runway 32 clear for the Boeing 737. This would mean some quick thinking to align for runway 35 and prepare for landing on a much shorter runway.

The student pilot’s initial reaction was that they couldn’t do it. The Cessna was too high and too close to the runway, now just 3.9 nautical miles from the runway threshold. The student had only landed on the shorter runway once before.

But the instructor quickly worked out, correctly, that they were in a perfectly good position to approach runway 35. The wind was coming from 010⁰ at 15 knots. For runway 35, that meant that they had a headwind component of 14 knots and a crosswind of 5 knots. This would be a good opportunity, the instructor thought, for the student to practice landing on a shorter runway.

The instructor responded to the controller: “Affirm.” Yes, they would accept the controller’s request. The controller cleared them for a straight-in approach to runway 35 at best speed.

Their speed still mattered because runway 35 crosses runway 32; the controller needed the Cessna to land and be clear of the runway before the Boeing 737 could be cleared to land on runway 32.

As the Cessna reached two miles from the threshold of runway 35, the controller cleared the Cessna for a visual approach, saying, “I need best speed all the way in to crossing the runway.”

The instructor had received instructions before for “best speed” but never “to the runway”. Still, he thought they could comply.

The first thing they needed to do was to reduce their airspeed to configure the aircraft for landing, so the instructor told the student to reduce the throttle to idle while lowering the aircraft’s nose to maintain best speed. The airspeed reduced to under 110 knots. The student extended the flaps to 10°.

On a normal approach, the pilot continues to extend the flaps as the airspeed reduces, so that the flaps are fully extended to 30° for the landing. In order to protect the structural integrity, the aircraft needs to be travelling below 85 knots for the pilot to continue to safely extend the flaps for landing.

But as the instructor wanted to ensure that they maintained “best speed” for the approach, they continued at 90 knots and did not extend the flaps further. The Cessna continued at 90 knots or higher for the rest of the approach with the flaps left at 10°. To keep the speed up, they approached steeply, at 5° instead of a stabilised approach profile of around 3°.

The advantage of having the flaps fully extended is the increase in drag, which slows the aircraft and allows for a steeper descent on approach and a lower touchdown speed.

The typical landing distance for the Cessna 172R with flaps fully extended is about 400-430 metres (1,300-1,400 feet). This meant that they were fine landing full flaps with the 582 metres on runway 35, especially with a 14-knot headwind.

A landing with the flaps only partially extended is not inherently dangerous; pilots often choose to land with 10° flaps, for example in crosswind conditions. Landing without the flaps fully extended requires more braking distance.

If they were landing on runway 32, as initially planned, 2,492 metres was more than enough runway to safely land and slow down, even if they used no flaps at all. Extending the flaps to the first stop of 10° still allowed for plenty of braking distance for them to touchdown at a faster speed.

However, the fact remains that a lower touchdown speed and less braking distance are very much considered positive characteristics for a short-field landing. Technically, a good pilot can land a Cessna in 177 metres, although more realistically in 408 metres, needed for a less shallow approach so that they would clear any obstacles up to 50 foot in their approach path. With the 14-knot headwind, the landing distance required dropped to 368 metres. Even a mediocre student pilot at the end of a long day should be able to land on runway 35 in these circumstances.

But 368 metres is assuming the aircraft is set up for a short-field landing: flaps fully extended at 30°, crossing the threshold at 62 knots with the power fully idle, with maximum braking on a dry runway).

Attempting to land at best speed with 10° flaps on runway 35 may have been possible for an experienced pilot, especially if there were no obstacles on the approach. But it certainly left no margin for error.

At one mile out, the Cessna was descending through 500 feet at 95 knots ground speed. The controller cleared the flight to land and instructed them to continue to taxi into GOLF, referring to the taxiway at the end of runway 35, shortly after the intersections of runway 32 and the parallel taxiway CHARLIE. The call confirmed that they were cleared to cross the runway 32 intersection. Once they were safely out of the way on taxiway GOLF, the Boeing 737 could land without concern.

But at the same time, the controller realised that they were approaching much faster than normal. It didn’t occur to the controller that they were attempting to maintain “best speed”. Instead, the controller presumed that the Cessna had decided to abort the landing on runway 35 and just hadn’t made the call yet. Probably with a slight sigh, the controller started a plan to re-sequence the Cessna for a go around.

The normal landing speed for the Cessna 172R is 61 knots with flaps fully extended or 66 knots with the flaps retracted. The FAA define a stabilised approach to be a constant-angle glide path within +10 and -5 knots of the recommended landing speed. If the approach is not stabilised or becomes unstabilised under 300 feet, the pilot should immediately initiate a go around.

The Cessna was travelling at 90 knots with only 10° of flaps to a runway with little room for forgiveness. A decision to abort the landing and go around for a second attempt once the Boeing was out of the way would have been a good plan.

However, as this was an intentional decision to comply with the instruction to keep best speed “all the way to crossing the runway”, the instruction didn’t consider the approach to be unstabilised and was happy to continue.

The student pilot continued to approach. They crossed over the threshold of runway 35 at 100 feet and 90 knots indicated airspeed (about 80 knots ground speed): fast and high.

The Cessna floated in ground effect just above the runway, which would have felt to the student like they were on the cushion of air. Finally, the wheels touched the runway, but only briefly. The aircraft bounced back into the air.

The instructor tried to reassure the student, saying to continue the landing rather than go-around.

This type of light bounce is easily recoverable if you have enough runway. I once gently bounced a Cessna 152 on Malaga’s runway three times and still had a few thousand feet in which to brake and turn off the runway. But the key here is “enough runway”.

The instructor, having lost some level of situational awareness, encouraged the student to continue as there was plenty of runway on 32 to recover the landing.

But they weren’t on runway 32. There was not plenty of runway left on runway 35.

Again, going around at this point would have been a good plan: after the bounce, the student pilot should have applied full power, followed by gently pulling back on the controls for a slow climb away.

Instead, the instructor had decided they should continue.

The Cessna touched down again, this time firmly. They didn’t have much runway left. The student applied full brakes.

Remember what I said about no margin for error?

The high speed landing and abrupt braking caused the wheels to lock up. The Cessna’s momentum kept it racing forward along the runway, the tyres skidding instead of rolling.

The instructor took control and pulled the control column back, hoping to increase the weight on the wheels and regain control of the steering. The Cessna continued along the runway at high speed. They raced through the runway 32 intersection.

The controller, watching from the tower, called “Turn up [taxiway] CHARLIE if need be.” It would be easier to turn left onto CHARLIE which would give them them a long and straight run, parallel to runway 32, in which they could slow the aircraft.

The instructor heard the controller’s call but couldn’t process the instruction quickly enough, already focused on making the sharp right turn onto taxiway GOLF.

As the instructor turned, the Cessna skidded left of the taxiway onto the grass, barrelling towards a drainage ditch.

It was now that the instructor decided that yes, maybe they should go around.

This was likely an instinctive reaction as they bumped over the grass with the drainage ditch visible before them. The instructor applied full power and pulled back on the control column.

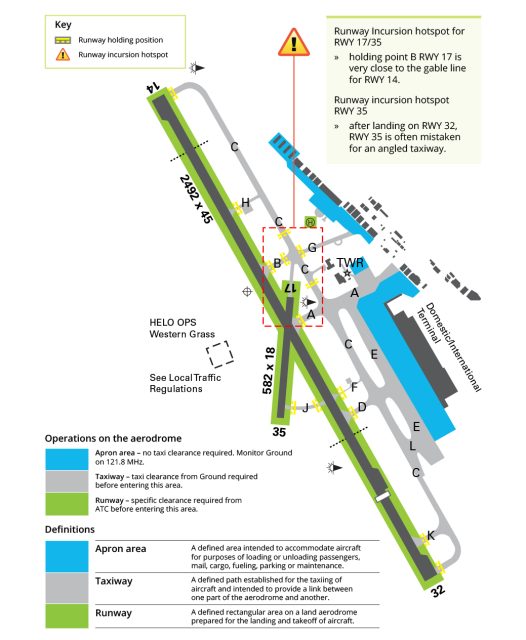

As the nose rose in response, the rear of the aircraft hit the ground.

Watching aghast from the tower, the Boeing 737 likely forgotten, the controller activated the crash alarm. This automatically declares an emergency and alerts emergency services.

The instructor continued on full power. The aircraft slowly climbed away, missing the drainage ditch. Now they were flying unsteadily towards a row of hangars.

Inside the cockpit, the stall warning horn sounded. The Cessna 172R’s stall warning sounds between 5 and 10 knots above the stall. Already at full power, their options were limited. But levelling out to increase the speed meant flying directly towards the hangars.

The instructor lowered the nose slightly and aimed for the lowest roof, hoping that they would clear it. The call to the controller seems unreasonably calm: “Just had to make an emergency go around.”

There’s no mention of the student pilot but if it were me, I can tell you that my eyes would have been firmly shut.

The Cessna cleared the hangars and continued to climb.

The controller passed the aircraft to another controller; the report does not explain why, but I assume it was for a quick change of trousers. The new controller informed the instructor that they had suffered a tail strike and asked whether they believed they could conduct a normal approach and landing. This is an entirely reasonable question: is your aircraft flying normally? Can we sequence you in or do you need emergency measures? But you’ll forgive me for imagining that the tone of voice for the question implied “as opposed to whatever the hell that just was…”

The instructor confirmed that, yes, they could. Now that they were clear of the hangars, there didn’t seem to be any pressing problems or issues as a result of their tumbling over the grass and striking the ground.

The instructor remained in control, entering a right circuit and circling once on downwind at the controller’s request, in order to allow for better spacing with other aircraft.

The Cessna landed on runway 32, the longer runway, safely at 14:34, about ten minutes since the initial decision to land at “best speed” on runway 35.

I’ve put best speed in quotes because, although this is a common request from controllers, it’s not actually clearly defined and is not listed as a standard phrase in the Airservices Australia AIP (Aeronautical Information Publication). Obviously, controllers must feel free to use the phrases that suit the moment, aiming for clear and concise plain language. And the truth is that every pilot knows that the point of best speed is that the controller wants you out of the way as quickly as possible.

In this case, the controller believed that if the Cessna conducted a normal approach, they probably would not have had time to land before the inbound Boeing 737, especially as training aircraft sometimes flew very slow approaches.

It was reasonable for the controller to ask the Cessna pilots if they could keep their speed up so that they would have landed and cleared the runway before the inbound Boeing 737 would be on final approach.

What the controller expected was for the Cessna pilots to keep their speed up for most of the approach but then reduce their speed to normal approach speed shortly before the threshold.

The point of “best speed” is that the pilot needs to decide what is the best speed that they can achieve to continue the approach and land safely. What speed is safe can vary based on the aircraft, the circumstances and the experience of the pilot. A stabilised approach can be up to 10 knots above landing speed, so a reasonable interpretation would be to maintain at least that speed, in this case 71-76 knots, until the last moment of the approach.

It would also have been perfectly reasonable for either pilot to say that they could not comply, for whatever reason. The controller then would have had to make a decision: ask the Cessna to abort the landing and go around to make room for the Boeing 737, or allow the Cessna to continue, taking the risk that the Boeing 737 would have to go around because the runway was not clear in time.

In this case, the instructor was happy with the runway change and maintaining best speed. The instructor wanted to help the controller by getting in quickly, so that the Boeing 737 was not impeded. This was agreed with the flight at 1,000 feet and about 1.9 nautical miles from the airport. There wasn’t a lot of time to think about it.

The problem was made worse by the phrasing of “best speed across the runway“.

The report doesn’t get into this, but I think that the controller was talking about rolling across runway 32 after landing. That is, I would have taken the controller’s statement to mean “please fly a high-speed approach and land normally, but once you have touched down, please don’t slow unnecessarily until you have crossed the intersection of runway 32.”

To be fair, the Cessna certainly did cross the intersection very quickly.

After the incident, the instructor said that it was important to be more assertive in future and tell air traffic control that they could not comply with maintaining best speed while conducting a normal approach.

This strikes me as being the wrong lesson. Maintaining best speed for the approach, that is, continuing at 90-95 knots and flaps at 10°, would have been fine if they were landing on the longer runway. But even having agreed to land on runway 35, continuing at 90-95 for the approach and slowing to 66 knots for the landing was still a viable option, as was further extending the flaps in the last moments of the approach.

Another option would have been for the instructor to agree to best speed and then be prepared to take control shortly before landing. Or, realising that they were crossing the threshold at 100 feet above the runway and travelling 25 knots above landing speed, the instructor could have instructed the student pilot to go around.

When the Cessna bounced into the air, the instructor lost sight of which runway they were on. The instruction to continue was a grave error, as it was no longer possible to safely land the plane; the instruction to continue was categorically wrong.

My point here is that the failure was not that the instructor complied instead of refusing. The instructor eroded their safety margins with every acceptance, leaving the student pilot to attempt a fast landing on a short runway under stressful circumstances at the end of a long lesson. The real error was the instructor repeatedly deciding not to break off and go around, despite the approach and landing being clearly outside of reasonable limits.

The AAIB’s final report concludes with the following contributing factors:

- The air traffic controller’s requirement to maintain best speed to the runway, combined with the instructor’s interpretation of the instruction, resulted in an excessively fast approach.

(again, fast enough that the controller, who had asked for best speed, assumed that they were aborting their approach to go around and simply hadn’t called their intentions yet.)

- Although the aircraft exceeded the speed for a stabilised approach, the instructor did not conduct a go-around prior to landing or while on the runway.

- The excessive landing speed resulted in reduced braking effectiveness and a loss of control during the turn onto the taxiway.

- Following the loss of control, a go-around was initiated to avoid a drainage ditch, resulting in a ground strike and near collision with hangars located on the eastern boundary of the airport.

As a result of this accident, the flight school has reviewed their procedures for stabilised and unstable approaches and reviewed the training material for instructors and students, including communication, decision making and assertiveness. The flight school also initiated discussions with the instructors about the training challenges at Gold Coast Airport and how to deal with non-standard ATC requests and clearances, including refusing clearances.

I have a bunch of questions outside of the remit of the final report, for example: what happened to the student pilot? There’s no mention of whether the student continued with flight lessons. I hope so, but with a different instructor.